DICK SWAAB: THE CREATIVE BRAIN

Dick Swaab (1944), a distinguished Professor of Neurobiology at the University of Amsterdam, is a leading authority on the human brain. Throughout his extensive career, he authored numerous publications, received many awards and honors, and wrote several bestsellers, including 'We Are Our Brains' and 'Our Creative Brains.' A conversation about the incredible machinery that is the brain and how it sparks creativity.

What is creativity?

DS: “Creativity is a brain process where old building blocks are combined to make something new.

The front part of the brain plays an integral role in this creative process. All day long, we’re bombarded with information. We’d go crazy if we tried to process all of that information. That’s why we have filters in the prefrontal cortex and the thalamus that allow us to focus on what is essential. That filter differs from one person to the next.

Some people have a wide open filter, which allows them to process an enormous amount of information. These people are very creative but also at risk for psychiatric problems because their ability to process information verges on the edge of what is humanly possible. Then there are people whose filters are so closed that there’s hardly any room for creativity, so they end up working as an accountant.”

"People who are in love can be very creative. Just think of the artist and his muse."

Can we open up that filter and allow for more creativity?

DS: “Alcohol works for some people. Others use L-dopa, a drug that is used in the treatment of Parkinson's disease. Oxytocin, the love hormone, also helps. People who are in love can be very creative. Just think of the artist and his muse.”

Are there also methods that have less of a negative impact on one’s health and well-being? Relying on drugs or alcohol just doesn’t seem ideal.

DS: “Being in a new environment is also very effective. In our institute , we send our Ph.D. students to other labs for a period of two years. The change of scenery and surrounding results in new ideas and impressions.

What also helps is taking a multidisciplinary approach: take people from different backgrounds to discuss a problem or concept in a safe environment.”

We can influence the filter. Is there anything else we can do to train our creative muscles?

DS: “In the 1960s and 70s, the 10,000-hour rule became popular, the idea being that you could master any skill if you put in the work and the time. That theory hasn’t held up. The level of creativity is determined by things that cannot be changed, namely your genetic makeup.

Then there’s your IQ. A rise in IQ corresponds to increased creativity, although that effect only works up to an IQ of 124.

Your character also determines how creative you are. And all those things are 50% determined at conception. And the other 50% in the very early developmental years.”

"The level of creativity is determined by things that cannot be changed, namely your genetic makeup.”

So it’s nature over nurture?

DS “That’s a misconception. When we say 50% is genetic, people tend to assume that the other 50% is upbringing. But the nine months we spent in our mother’s womb, plus those early stages of development, also determine a lot. We come into this world with many character traits ingrained in us already.

And then there’s this thing called self-organization. The brain, like any complex system, organizes itself. That makes every brain different and unique. If you’re lucky, you make special connections in that early process and end up with a specific talent, although that usually comes at the expense of other qualities. By attending school and receiving an education, we discover what we’re good at and if we have any talents.”

We're trying to find a one-size fits all solution to increasing one’s creativity, but I’m beginning to understand that there is no such thing, right?

DS: “No, there isn’t. Every brain is different and needs different stimuli. Friedrich Nietzsche famously said, ‘All truly great thoughts are conceived while walking.’ Long walks worked for him, but that doesn’t mean they work for all. Some people get ideas while fast asleep. I’ve tried going to bed with a notebook and pencil on my nightstand, just in case I wake up with a brilliant idea. But, unfortunately, I have yet to write anything down.

So what works for some doesn’t necessarily work for everybody. Although, in general, it helps to set the mood and create an environment where people feel good, where they can have fun and dare to think out loud and make mistakes.”

You’ve mentioned in your book ‘Our Creative Brains’ that having a history of psychiatry in the family also helps when it comes to creativity. How so?

DS: “Ideally you want a history of psychiatric disorders in the family without suffering from any yourself. That way you have a genetic background that results in a different kind of brain that can make unique, more creative, and unexpected combinations."

That plays into the old stereotype of the troubled artist who suffers for his work and whose genius borders on madness.

DS: “Yes, except it’s not a stereotype. There are a lot of good artists who are bipolar. Take composer Robert Schumann. He was bipolar and when he was depressed, he didn’t produce anything. However, when in his hypomanic state, he created an enormous amount of work. He was composing day and night, only to fall back into a depression.

Not all brain disorders lead to more creativity. People who have schizophrenia tend not to be very creative. But when you look at a movement like Art Brut you do see neurodivergent people who aren’t trained artists but whose work is incredibly creative. And for them creativity works as a kind of medicine.”

Speaking of medicine: some people fear medication to aid their psychological distress will effect their creativity. Is there some truth to that?

DS: “Yes, there is. A big pharmaceutical company published a book composed of works of art that were made before and after the makers took psychotropic drugs. The company wanted to show the effectiveness of their medication, but art critics generally agreed that the works that were made before the artists took medication were far more interesting.”

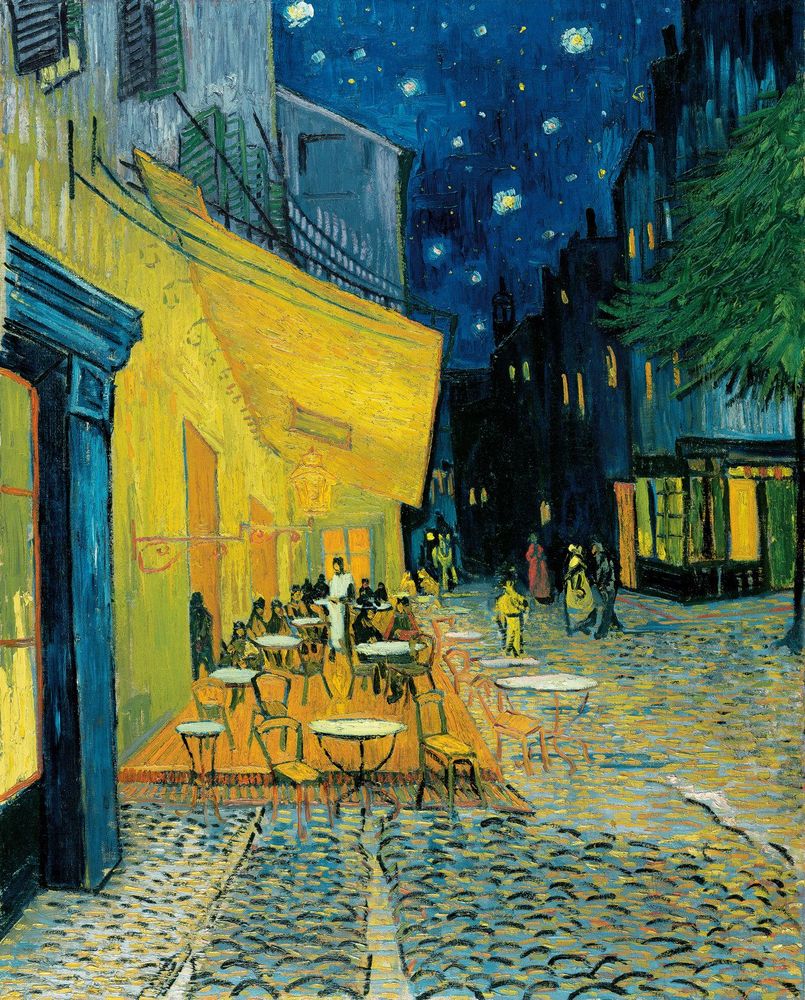

Well, that’s depressing! So some people really do have to suffer for their art, then? It’s wonderful to have these masterpieces that the general public can enjoy, but it comes at a huge personal cost for people like Schumann or Van Gogh.

DS: “If Van Gogh had been given modern-day treatment, we wouldn't have a Van Gogh museum. Van Gogh knew he would always be half crazy. His brain functioned differently, but because of that, he could make new combinations and create something completely new.”

If Van Gogh had been given modern-day treatment, we wouldn't have a Van Gogh museum

In recent years, employers began to see that they could gain from hiring workers on the spectrum, which has taken away some of the stigma associated with neurodivergence. Given what we now know about the brain and creativity: could the same happen to people with psychiatric disorders?

DS: “It’s the very reason why I wrote books for general audiences. I wanted to do something about the stigma and taboo that comes with brain disease. When you learn what a fantastic machine the brain is and the molecular biology behind brain development, it’s a surprise that people turn out reasonably well on the whole. It is such a complex mechanism and so many things can go wrong. Autism is a good example. Sometimes people on the spectrum have difficulty making eye contact or communicating with someone face to face, but they can communicate perfectly over the Internet or can focus on one particular task. At the Philips laboratories and at the Technical University in Eindhoven relatively more employees were on the spectrum. These people ended up marrying one another and having kids. And because autism is 70% genetic, there is a huge spike in autism in Eindhoven and surrounding areas.”

How do you, as a man of science, look at AI's developments and their effect on creativity?

DS: “AI is a huge hype right now, but it’s not creative. Nothing good comes out of it and computers aren’t taking over. AI takes over simple tasks that we would like to get rid of. Routine chores we’re not interested in. AI can carry out a certain assignment in a short amount of time and ad infinitum. A computer program can beat anyone at a chess game or checkers if programmed to do so. But you can’t surprise it with a game of snakes and ladders.

I also don't see AI writing a really good novel because it lacks the emotions that a human has.”

For now at least.

DS: “No, I really don't see that happening. AI is good with big data and pattern recognition, but not with emotions. And you need emotions for art. There was a monkey in London Zoo, and he created works of art that fetched a lot of money, and even Picasso and Matisse were interested. But when you saw the monkey at work he was like a 3-year-old, just churning out work after work in great succession. There was no emotion in it at all. And you need emotions to make something special.”

So in conclusion, I don’t have to fear AI just yet because as a human, I have something special, namely emotions. But how about the story I’ve told myself: that I’m creative because of my upbringing or the constant exposure to art. Is there any truth to that narrative or is my creativity simply the result of a genetic lottery?

DS: “You can come up with any narrative you like. That’s what we do. As humans, we have a number of useful illusions we tell ourselves and one of them is the illusion of free will. The other, that life makes sense.

In the end, every human being is unique, every brain is unique. But it's not unique to be unique. Everyone is unique.”

Comments