ED TEMPLETON: RAW CREATIVITY

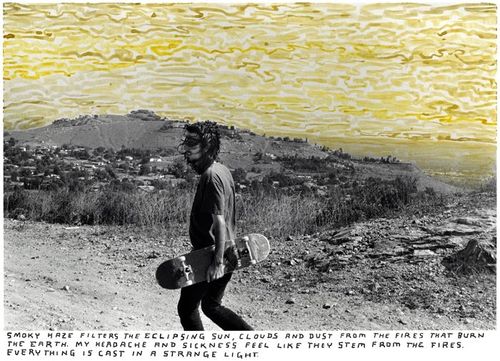

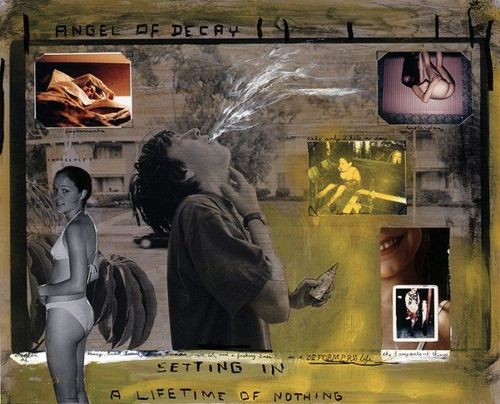

California-native Ed Templeton (1972) is a lot of things. Professional skateboarder. Two-time World Skateboarding Champion. Owner of skateboard company Toy Machine. Renowned (street) photographer. And acclaimed contemporary artist. He was one of the original Beautiful Losers who helped shape and capture the skate scene in the 1990s and has spent the last 20 years on a unique artistic and aesthetic journey.

“Skateboarding was definitely a creative outlet. The physical act of skateboarding is pure creativity.”

Were you always creative, even as a kid?

ET: "I think so. But to be honest, I don't even know if I think of myself as creative. I guess I am, based on my life and what I've done. And people tell me I'm creative, but I don’t walk around thinking I'm a creative guy or something. It's all been problem-solving within given structures."

What is your definition of creativity?

ET: "For me, creativity is mostly building on existing structures. Let's say you want to create a completely new piece of music. Something nobody has ever heard before, something completely foreign. Chances are you're going to alienate a lot of people simply because there will be no reference point. There will probably be some people who will think it is genius. But most people would consider it too far out in left field. In my example you need an existing song structure with a beat and lyrics, and then you can play with, and tweak those elements. And to me, creativity lives in that structure."

I love the music analogy, but how does that correlate to your own work?

ET: "Over the years, I've been asked to design skate shoes and the box they come in. And then you realize that within that structure, there's not a lot of wiggle room. I mean, a shoe is a shoe. There's not a lot you can do. You’re not going to reinvent the wheel there. In the end, everyone wants to have a shoe that works and that they can skateboard in. So all you're changing is the materials on the shoe, the look of the shoe, and then maybe the box. So it's extremely limiting in some ways. But that's where the creativity comes in. You try to come up with new ways to push what is possible within the given parameters.”

So, creativity requires constraints?

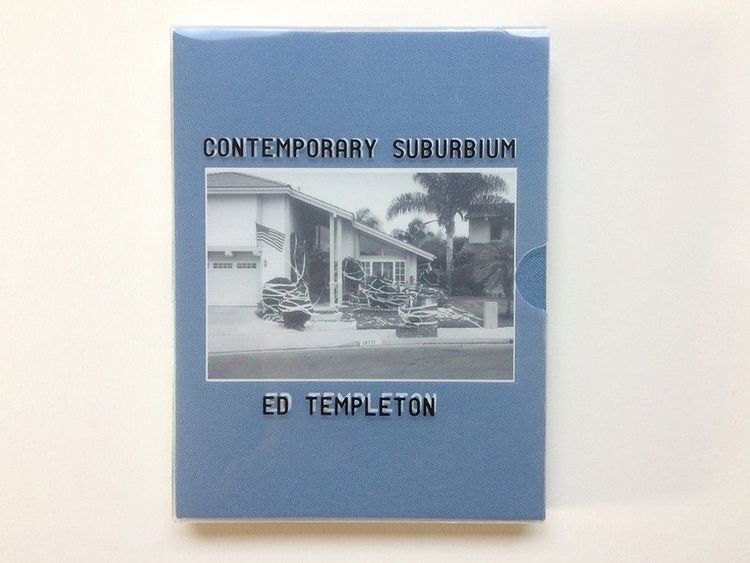

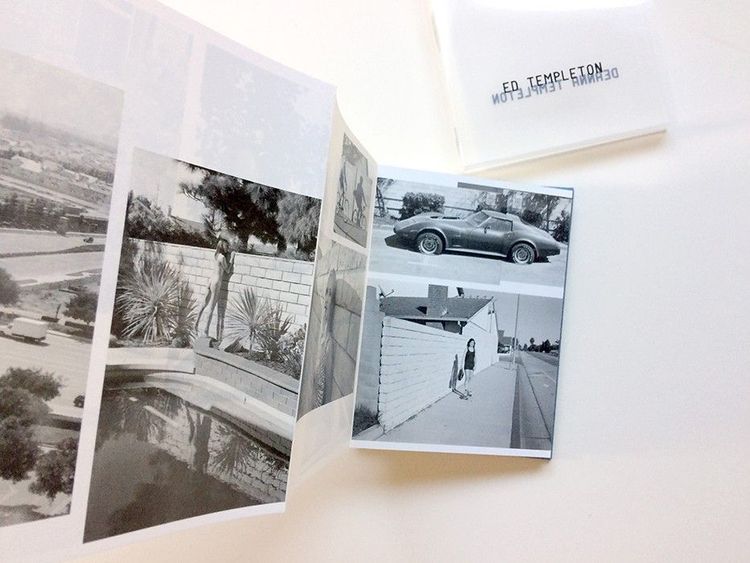

ET: "It doesn’t require them, but in reality most creativity is done within them. I'll give you another example. I make photo books. And so I'm constantly thinking about how to do something different with my books. I want my books to look different from every other photo book. But I also don't want to go so far where I'm just doing something crazy for the sake of it. So, I try to do something a little different. My bigger books are more traditional, like the recent one that just came out, but I do try to play with the structure of what's possible. But the book is only a conduit for the pictures themselves, it shouldn’t be about the book, but about the pictures. Again, very limiting, but that’s where the fun is, trying to make it your own. Deanna and I made this accordion-style book together, and I got a lot of praise for the fun design, but in all fairness, that wasn't me. My publisher came to me and said that one of his artists was making a very specific size book, which meant he was left with a big strip of paper trimmed off these giant sheets that would be wasted. He asked me if I had any ideas for that. So, I can't claim any creative genius there. It was just problem-solving. Someone came to me and said, hey, I don't want this paper to go to waste, and I happened to have a project that would fit nicely on the strip of wasted paper. It was a win-win situation: no wasted paper, and we got to make a cool book. Problem solved. But the amazing thing is that the photographs in that project were chosen to be exhibited at the Pier 24 Photography Museum in San Francisco, and eventually ended up in the collection of The Museum of Modern Art in New York!"

“Creativity is also being ready for those opportunities when they come."

The ripple effect is in full swing.

ET: “Yes. Creativity is also being ready for those opportunities when they come. With the book, a strange opportunity arose. If I hadn't had an idea, someone else would have taken that strip of paper and done something with it. But I was ready at the moment. And that's a big part of creativity: being ready for it. It's what athletes always say: be ready for the moment. Have projects you're juggling and working on and thinking about all the time so that when that opportunity arises, you have something to fill it.”

Speaking of juggling work. You make books. You work as a photographer. You have your own skateboard company. You create works of art. In short, you have a lot of different canvases to work on. How does that work in your brain? Do you have an idea and then figure out what outlet works best? Or is your work much more compartmentalized?

ET: "It is a little bit compartmentalized, although there's been a lot of bleed-over through the years in different ways. But the compartmentalization has almost always been part of it. The art I make for skateboard graphics is so different from the paintings I do or the skate photographs, which are much more grittier. So on the creation side, it is very compartmentalized, but it doesn't work that way in my brain: there, it's much more fluid.

The thing is, all these outlets have a different audience. So when I'm doing a skate graphic, I get into a skateboard mindset, and I think about me as a, you know, a 15-year-old boy going into a skate shop. And how I loved looking up at the boards and checking all the graphics and everything like that. So when I get in my skate world, I get into my skate head. There have been crossovers where I'm doing something in the fine art world, and an idea pops up for a skateboard graphic, and there have been times when I've used drawings that I've done as skateboard graphics. So, my fine art practice blends into my skateboard practice. Funnily enough, it doesn't go vice versa a lot. I don't usually find something in the skateboard world that I bring into my art."

What does your creative process look like? Where do you get your ideas?

ET: "I end up coming up with a lot of ideas in the shower. I think a lot of people have this experience. The shower is an important creative space because it's just you and your thoughts. Sometimes, if I'm trying to think of a new idea, I look forward to just taking a shower cause I know all distractions are taken away. You don't have your phone, and there's no TV. You're just standing there thinking about something, and a lot of times that creates the brain space to create a new connection."

You mentioned athletes earlier on, and how creativity is similar to sports in that you must be ready when the moment comes. So, to continue the sports analogy: is creativity a muscle you can train and improve or something you are born with?

ET: "I really think that you're either born with it or not. I don't think I was a natural skateboarder. I wasn't born to skate like some people whose style is effortless and easy. I was never that guy. I had to work. I had to practice. And I had to think about it. I had to try hard. All those tricks you see of me in a video were multiple tries and multiple injuries. And creativity works the same way. Some people are born with it and make it look effortless; others must put in the hours, train, and work hard.

And when it comes to creativity, I suppose I fall in the 'was born with it' category, but I also put in the work. My brain is always thinking of something. I'm constantly creating graphics and thinking of graphic ideas."

“If I have an idea to do something, but it might not sell very well, we'll do it anyway.”

And does that ever wear you out?

ET: “No, it's fun. I would rather have too many ideas than have no ideas. I have so many ideas that I have to pick and choose what I will work on. There are crunch times when too much comes together at once, and I feel like I’m on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Or I get a terrible headache.”

The work you do is very diverse. You make contemporary art but also run a skateboarding company. How do you strike the right balance between commerce and creativity?

ET: "Commerce is always back of mind. But I feel lucky that in my fine art practice and even in the skateboard company, which is a purely commercial endeavor, I don't have to think about commerce that much. If I have an idea to do something, but it might not sell very well, we'll do it anyway. Like, every year, we do a Halloween deck. And we'll usually do something crazy, like a weird shape or something. It's impractical, but enough people will like it that we make a small run. So I don't feel hampered by the idea that we can't waste money on this or that."

And how is it having a spouse who is also creative? [ed. artist and photographer Deanna Templeton] I assume it's great because you continue to work together, right?

ET: "Yeah, it's really wonderful actually. Street photography can be really weird: we walk around with a camera, pausing and trying to get a photo without people noticing it. But one of the great things about having a photographer wife is that she understands what I'm doing and is an ally. We help each other on the streets a lot, you know. I'll sometimes create a distraction for her. She'll see like a cool old man smoking, hanging out a window. And I'll walk up and pause and pretend I'm looking at my map on the phone like a tourist, and then she'll get behind me to focus and get her exposure right. And then maybe I'll move. And she'll come out and shoot. And she does the same for me. I'll be shooting a photo, and maybe someone sees me and gets a little weird, and then she will come in and say something like: 'Ohh, your dress is so cute, or something like that.' And that just breaks the ice. So yeah, we work together in that way. It's kind of interesting and fun."

Is there any competition between you two? Like when one spots something before the other does?

ET: “Yeah, that's the downside of working together. I usually let her have the shot, simply because I shoot so much more than she does. For the last couple of years, Deanna has been a lot more passive in comparison. For instance, we went to Europe over the summer and she shot 10 rolls of film, while I had 70. There have been times when we had little arguments about who shot what. And sometimes we just decide to both shoot something. And whoever shoots its best gets to use it.”

What does the selection process look like? You use film rolls, so you only know what you have once you develop them.

ET: "I just got all my photos from our European trip—all 70 rolls. And my first reaction is always super negative. I looked at everything, and I went *** **** it, I didn't get anything. Almost all the photos that I thought would be cool weren't, and then I got super depressed. And it's the same process every time. Then, I'll scan the proof sheets and start going through the process of archiving them digitally. And as I go through that process, I soften a bit, and I'll start finding things I like. Things I didn't notice the first time around.

My wife wanted to throw away a bunch of her negatives. She figured that someone would find them after her death, judge her, and think of her as a crappy photographer. And I forced her to hold on to those negatives. So she put them into a separate album called her “crap book.” And now it's like this running joke between us because, over the years, she has found so many good photos in that album. The thing is, over time, things change. I might not have liked a photo then, but maybe now, for instance, the building in the picture isn't there anymore, so the shot has become interesting on a historical level."

“Shooting on film is more expensive, and it's kind of a pain in the ass, but I prefer it.”

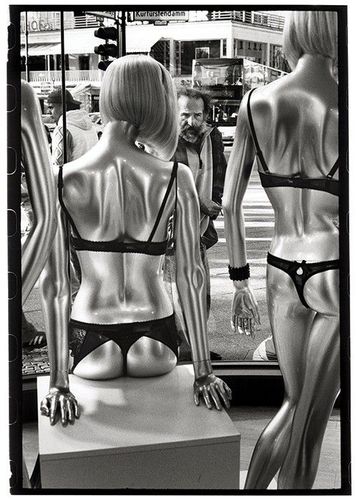

Why do you insist on working with film rolls, dark rooms, and a lengthy editing process when you can use a digital camera, take the shot, and immediately see your work?

ET: "I just prefer film. I'm not anti-digital. Look at my Instagram, and you'll see I use my iPhone to shoot all the time. But my iPhone and film photos are wildly different just because of the technique and because the lens on the iPhone is so wide. Also, everyone has a phone, so it's almost like you're invisible while shooting. You can walk by people at full speed and snap a photo. But taking a picture with my thumb without anyone noticing it is different from raising a camera to your face. Everyone sees that and feels that, but no one feels an iPhone because everyone in the world has one in their hand at all times.

I've been thinking about buying a digital camera to do commercial jobs. But the funny thing is that the people who hire me for commercial jobs hire me because I shoot film. And so they know what they sign up for, that it takes a couple of days to see results. But those commercial jobs can also be stressful because I don't know what I shot and don't know if I did the job correctly. It's one thing to shoot photos for myself. If I mess up, no harm is done or money wasted. But messing up a commercial job is scarier, so going digital would make sense.

But the digital question is hard for me because I don't have any real answer other than to say I prefer film. Shooting on film is more expensive, and it's kind of a pain in the ass, but I prefer it. And I can afford it. I like the idea of film. I have a dark room at my house so that I can print the photo myself. And I enjoy the physicality of it. The realness. And I like that the print itself often becomes an object. I will write on the print or on the edges."

“When I'm in my studio, away from the phone, I usually have a good time.”

What would you consider creativity killers?

ET: "My iPhone is the creativity killer. I spend too much time on that thing, and every time I'm done looking at it, I realize I just fried my brain because all I did was look at other people's creativity on Instagram. And then I get depressed because I just saw all this cool stuff everyone's doing. And it's unfair because you only see everyone's best projects and work. So I usually regret spending time on my phone, time that I could have used to make a book or a painting or read a classic book. And yet I return to that phone every single day."

And what fuels your creativity, other than lengthy showers?

ET: "When I'm in my studio, away from the phone, I usually have a good time. Painting is repetitious; you're just sitting there making these little strokes for an hour and listening to music or a podcast. Those are good kinds of moments. It's not that different from taking a shower.

And then there's sleeping. It's like the equivalent of a shower: you lay there, and all the distractions are gone. And you close your eyes, and you're in that black void. Your brain creates things. It's all black, so you have to imagine everything. And so if you start thinking of something you want to do, be it a book, a graphic, or something new in an exhibition. Sitting in that black void, your brain naturally goes into a zone where you think of something, and that's how you grab it. That's idea formation. Your brain creates an anomaly. What sucks, though, is half the time I wake up not remembering the idea."

You make books yourself: any books that have inspired you on your creative journey?

"One of the most super inspiring books is Jim Goldberg's 'Raised by Wolves.' It's about runaway kids. And that book has been a touchstone for me, but I hate citing it because it's almost impossible to get a copy. You might find one online, but it might be like $1000."

Do you have any favorite albums or podcasts you listen to while working that help you to be more creative or productive?

ET: "It sounds super boring and weird, but I'll often just have NPR on. [ed. NPR is National Public Radio, an American public broadcast service] It's really dry a lot of the time with news and local stuff. But to me, it's kind of like white noise. And it's the same with television. When I'm drawing in the living room, the TV will be on, and I'm sitting sideways from it. There will be some show on, like a rerun of The Office, but it's just background noise. But I never look at it.

But then, once in a while, I'll be like, what the hell am I doing? And then I'll put on music, which has an immediate effect. It has even changed the way I paint. The attitude of a song changes my attitude as I paint, and I've actually felt myself take more risks with what I'm drawing while listening to a punk song."

"It's all been trial and error."

You're a self-taught artist. What sparked your interest in art in the first place?

ET: "In high school, I had an art class. But yeah, I never went to college or anything. Just the School of Hard Knocks. [laughter] I've always just had to learn from books and from looking at other paintings, and you know, you try something, and you see if it works, and sometimes it does, and sometimes it doesn't. It's all been trial and error.

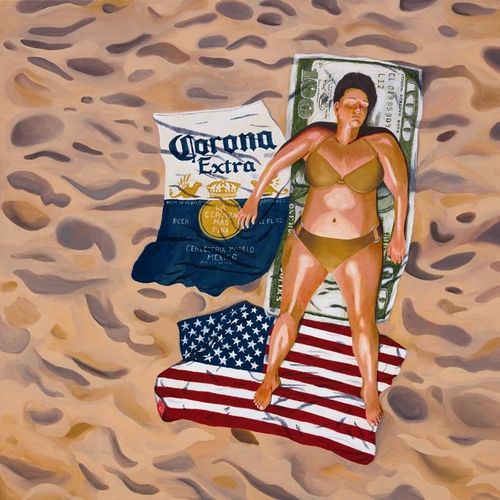

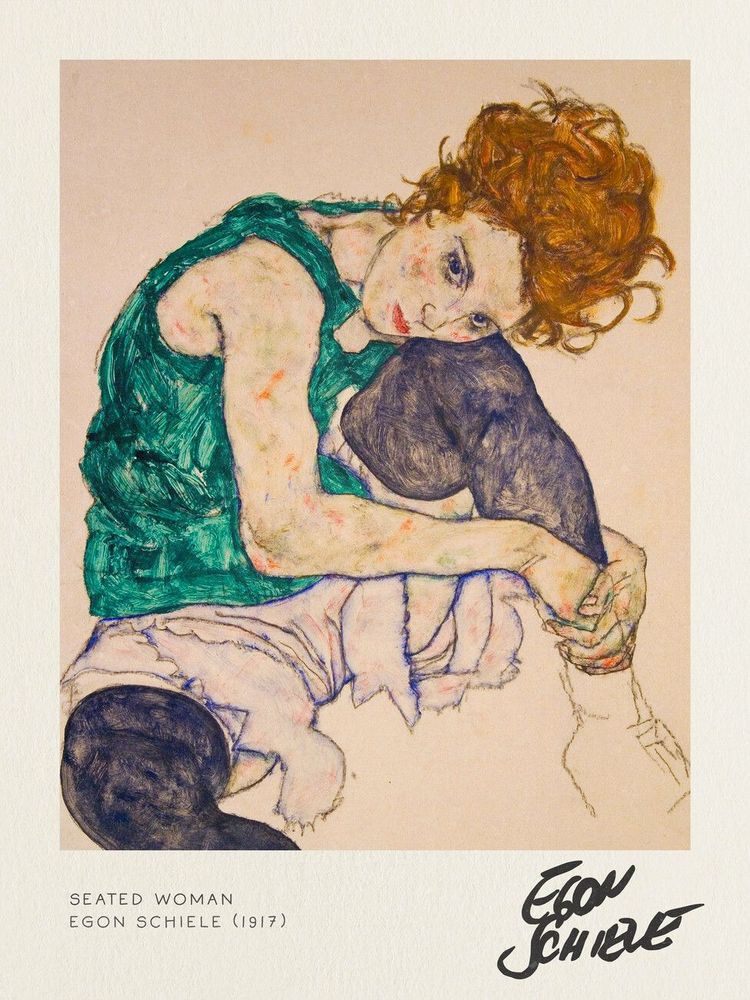

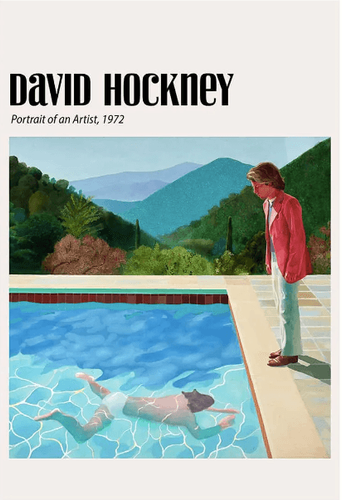

In high school, my grandparents would take us to the mall, and there was a Rizzoli bookstore there with a pretty good art section. And I found this little book on Egon Schiele, and my mind exploded. I thought it was really cool. My grandparents took us to museums, so I was aware of the famous artists and everything, your Van Goghs and Monets. But Schiele's work was such a departure from all of that, with the scraggly lines and angst in the works. I learned about Austrian Expressionism and became a big fan of all these Austrian painters from that period. And I still like those guys, but then I also discovered David Hockney, which resonated with me because of living in Southern California."

And let's remember that at the same time, you were making a name for yourself as a professional skater. Did creativity play a role in that as well?

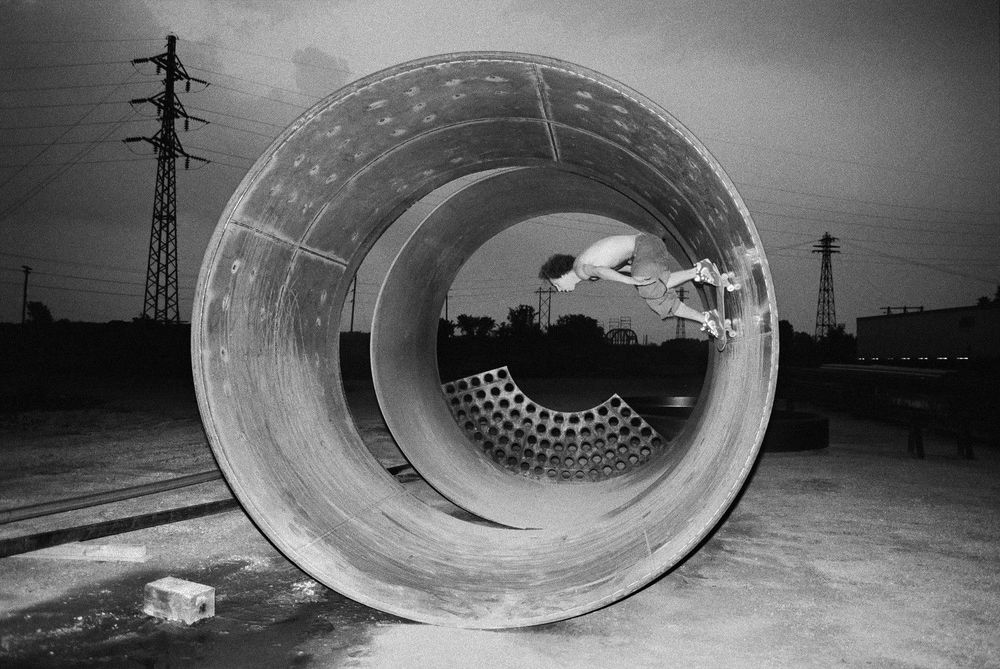

ET: “Skateboarding was definitely a creative outlet. The physical act of skateboarding is pure creativity. Can you imagine the creativity bursting out of Mark Gonzales’ brain in the early 80s when he invented half the tricks we all do today? I was constantly juggling all these different things. I was running Toy Machine while being a pro skater and couldn't do either to the best of my abilities. I was always hard on myself because I wasn't the pro skater I could be. And I still wonder sometimes, what if I just decided to stop photography and focus on my painting? Could I become a great painter? And vice versa with photography, or even Toy Machine.”

So why haven't you focused on one thing?

ET: “I think choosing would be hard. I opened up all these accounts and now must maintain them. So I painted myself into a corner on that. But then also I think if I was only doing one of those things, I might burn out. And so I feel fortunate that I can go into painting mode for a while when I have a show coming up. And I go into skate graphic mode at times, etc.”

But all these pursuits require a different focus on your part. Spending a day painting in the studio is different from the day-to-day running of a skateboard company. That requires some flexibility and a different work mode or rhythm.

ET: "That comes naturally. When I have an exhibition coming up, I have a goal: I need to finish a certain amount of paintings before the show's opening. So, I tend to go into an all-day mode where I wake up and paint all day. But on typical days, I might go in the studio and paint a little bit, then work on my photo archive for a while, and then work on skate graphics too."

Speaking of archives, what are your favorite clips of your skateboarding?

ET: "My favorite has always been the Emerica, ‘This is Skateboarding’ video. I was probably at the height of my power. That's the best skating I did as far as, like, physical tricks. I did a lip-slide on an 18-stair handrail, which was, at my age, pretty cool. Looking back, the tricks I did in that video were probably the best I could do. Although I never truly became the best I could be because, like what we discussed before. I never dedicated the time. If I look at my peers, they just lived and breathed skateboarding and realized their potential much more than I did. So I'm sad about that sometimes.

The same applies to art. I could be a better painter if I devoted more time to it. Photography is different because I do spend a lot of time shooting. It's the one constant thing because I always carry a camera. But I might go six months without painting, and then I'll get back in the studio, and it feels like I'm starting all over again. And it's tough. Cause just like I'm not a natural skater, I don't think I'm a natural painter. I don't have that gift. I can't just make paintings happen. I have to work for it."

“Self-doubt is a normal and healthy byproduct of putting your work out in the world for people to see. It’s scary, but you have to overcome it.”

Isn't that self-doubt an intricate part of the creative process? It certainly is something that most of the creatives I've interviewed experience.

ET: "It's completely normal to feel this way, and I've come to terms with it. I tell myself that what I left behind is good enough. You'll always feel like you could do better, but I can look back at skating and go, OK, I don't think I reached my potential, but I'm still in the skateboard hall of fame! [laughing] I still was the world champion two times! At some point, you have to realize you can only do what you can do. I think self-doubt is a normal and healthy byproduct of putting your work out in the world for people to see. It’s scary, but you have to overcome it. Think of the people who have no self-doubt at all; they must be psychopaths."

Comments